Wildlife Wednesday: Recent Butterfly Sightings at the Nature Center

Springtime is a great time to see butterflies at the Nature Discovery Center. You may see one fluttering through the forest, visiting our wildflower gardens around the Henshaw House, or flitting from flower to flower in the Pocket Prairie. In this week’s Wildlife Wednesday, we’ll have a look at few species of butterfly that have appeared over the last few weeks.

Gulf Fritillaries (Agraulis vanillae, above photo) are  one of our most common butterflies in the park. Not actually related to other fritillaries, these butterflies are actually a kind of longwing or Heliconian butterfly. While the adults will feed on nectar from a variety of flower species, the larvae (caterpillars) will only feed on passionvines (Passiflora spp., Left photo). Passionvine leaves are toxic, and in turn the caterpillars are toxic, as are the adults. The bright orange and black coloration acts as a warning. Gulf Fritillaries have a wingspan of about 3.5 inches.

one of our most common butterflies in the park. Not actually related to other fritillaries, these butterflies are actually a kind of longwing or Heliconian butterfly. While the adults will feed on nectar from a variety of flower species, the larvae (caterpillars) will only feed on passionvines (Passiflora spp., Left photo). Passionvine leaves are toxic, and in turn the caterpillars are toxic, as are the adults. The bright orange and black coloration acts as a warning. Gulf Fritillaries have a wingspan of about 3.5 inches.

Another common species of butterfly in this park is the large black Spicebush Swallowtail Butterfly (Papilio troilus), which can often be seen flying in an undulating manner through the forested sections of the park, but is really common all over. These large black butterflies have a 4 inch wingspan, and often fly close to the ground. The larvae feed on plants in the Laurel family, like Sweetbay, Red Bay, Spicebush, and non-native Camphor trees.

A butterfly that is not so common in the park, but that recently made an appearance is the gorgeous little Long-tailed Skipper (Urbanus proteus). We saw one feeding on white clover flowers near the Pocket Prairie a few days ago. These blue and brown butterflies have long projections on the hindwings, which look like 2 tails. They lay their eggs, and the larvae feed on plants in the legume family, like wild peas, wisteria, beans, and various others.

A butterfly that is not so common in the park, but that recently made an appearance is the gorgeous little Long-tailed Skipper (Urbanus proteus). We saw one feeding on white clover flowers near the Pocket Prairie a few days ago. These blue and brown butterflies have long projections on the hindwings, which look like 2 tails. They lay their eggs, and the larvae feed on plants in the legume family, like wild peas, wisteria, beans, and various others.

Thanks for joining us for another Wildlife Wednesday! Come out to the park soon, and see if you can spot some of these butterflies in the wild.

See you soon,

Eric Duran

Staff Naturalist

photos: Gulf Fritillary and Passionflower by Eric Duran; Spicebush swallowtail by Greg Hume | Flickr; Long-tailed Skipper by John Flannery | Flickr

The Three-toed Box Turtle (Terrapene triunguis) is our most common species of turtle, and is therefore the one you’re most likely to see. As with most box turtle species, they’re terrestrial, and tend to be associated with forested and semi-forested habitats. They are rather omnivorous, feeding on a wide variety of mushrooms, berries, flowers, insects and other small invertebrates. Also like other box turtles, their lower shell (the plastron) is hinged, which allows them to pull inside their shell and then close it up tightly. Three-toed Box Turtles usually have a caramel colored shell, which may have darker markings as well, and the males will will have various colorful markings around the face and legs. Males are larger and have reddish eyes, and the females have yellowish eyes.

The Three-toed Box Turtle (Terrapene triunguis) is our most common species of turtle, and is therefore the one you’re most likely to see. As with most box turtle species, they’re terrestrial, and tend to be associated with forested and semi-forested habitats. They are rather omnivorous, feeding on a wide variety of mushrooms, berries, flowers, insects and other small invertebrates. Also like other box turtles, their lower shell (the plastron) is hinged, which allows them to pull inside their shell and then close it up tightly. Three-toed Box Turtles usually have a caramel colored shell, which may have darker markings as well, and the males will will have various colorful markings around the face and legs. Males are larger and have reddish eyes, and the females have yellowish eyes.

The only species of aquatic turtle that lives in our park is the Red-eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans), which is also one of the most commonly encountered aquatic turtles in the Houston area. This is one of the “basking turtles”, aquatic turtles in the family Emydidae that are often seen basking in the sunshine on pond banks, rocks, and logs. Sliders are ominvorous turtles, but start out their lives as primarily carnivorous, and shift to a more plant based diet as they grow older. Despite the name, the red marks on the sides of their heads do not correspond exactly with the location of the ears. While the shells of the juveniles may be elaborately marked with yellow and green lines, the patterns fade away (eventually to black or dark gray), as they mature. Older individuals may even lose all markings and become totally black (a color condition called “advanced melanism”).

The only species of aquatic turtle that lives in our park is the Red-eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans), which is also one of the most commonly encountered aquatic turtles in the Houston area. This is one of the “basking turtles”, aquatic turtles in the family Emydidae that are often seen basking in the sunshine on pond banks, rocks, and logs. Sliders are ominvorous turtles, but start out their lives as primarily carnivorous, and shift to a more plant based diet as they grow older. Despite the name, the red marks on the sides of their heads do not correspond exactly with the location of the ears. While the shells of the juveniles may be elaborately marked with yellow and green lines, the patterns fade away (eventually to black or dark gray), as they mature. Older individuals may even lose all markings and become totally black (a color condition called “advanced melanism”).

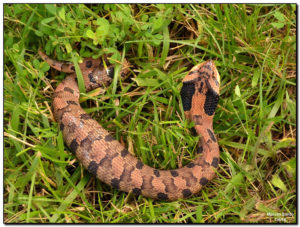

The Eastern Hognose (Heterodon platyrhinos) is one of the few creatures that can eat toads (with their toxic skin). Hognoses are (mildly) rear-fanged venomous, and use those fangs in the rear of their mouths to pop the toads which they eat (toads inflate themselves with air to keep from being swallowed). These snakes are known for spreading their hoods, like a small cobra, and hissing loudly when threatened. If that doesn’t drive away a potential predator, they flip over and play dead (even letting their tongue hang out and emitting a foul death like odor).

The Eastern Hognose (Heterodon platyrhinos) is one of the few creatures that can eat toads (with their toxic skin). Hognoses are (mildly) rear-fanged venomous, and use those fangs in the rear of their mouths to pop the toads which they eat (toads inflate themselves with air to keep from being swallowed). These snakes are known for spreading their hoods, like a small cobra, and hissing loudly when threatened. If that doesn’t drive away a potential predator, they flip over and play dead (even letting their tongue hang out and emitting a foul death like odor).

The Green Anole (Anolis carolinensis) is the most commonly seen native lizard in the park. Also called Carolina Anoles, they are sometimes called “chameleons”, because of their ability to change skin color (various shades of green and brown). However, they are not true chameleons, which are found in Africa, the Middle East, and Southern Europe. Green Anoles are conspicuous lizards and excellent climbers, often sunning, fighting, feeding on insects, courting and mating on the sides of houses, fences, trees, bushes, and yard furniture. The males are easy to identify with their pink dewlaps (throat fans) which they extend when trying to court a female or making territorial displays to other males.

The Green Anole (Anolis carolinensis) is the most commonly seen native lizard in the park. Also called Carolina Anoles, they are sometimes called “chameleons”, because of their ability to change skin color (various shades of green and brown). However, they are not true chameleons, which are found in Africa, the Middle East, and Southern Europe. Green Anoles are conspicuous lizards and excellent climbers, often sunning, fighting, feeding on insects, courting and mating on the sides of houses, fences, trees, bushes, and yard furniture. The males are easy to identify with their pink dewlaps (throat fans) which they extend when trying to court a female or making territorial displays to other males.

enal’s Duskywing (Erynnis juvenalis) is one of 2 species of Duskywing (dark colored skippers that keep their wings open and flattened when on a perch), found in our park. The other is the very similar Horace’s Duskywing, though there are many other species of Duskywing across the country. The caterpillars of these skippers feed on oak leaves. They are similar in size to the Checkered skippers, ~3.8 cm wingspan. Duskywings can make themselves rather conspicuous with their darting, climbing, and diving flight patterns, and their habit of sunning out in flat open meadows in plain sight.

enal’s Duskywing (Erynnis juvenalis) is one of 2 species of Duskywing (dark colored skippers that keep their wings open and flattened when on a perch), found in our park. The other is the very similar Horace’s Duskywing, though there are many other species of Duskywing across the country. The caterpillars of these skippers feed on oak leaves. They are similar in size to the Checkered skippers, ~3.8 cm wingspan. Duskywings can make themselves rather conspicuous with their darting, climbing, and diving flight patterns, and their habit of sunning out in flat open meadows in plain sight.

Gulf Coast Toads (Incilius nebulifer) are the most commonly seen yard frog in our area, that’s because, like most toads, they are

Gulf Coast Toads (Incilius nebulifer) are the most commonly seen yard frog in our area, that’s because, like most toads, they are

Another frog that one hears calling in the park occasionally is the Green Treefrog (Hyla cinerea), the only treefrog we really see in the park. Despite the name, these bright green frogs are found mainly in reeds, grasses, and other vertical vegetation along the edge of freshwater ponds and marshes. During warm Spring and Summer months the males sing a raucous chorus of nasal KWAK KWAK KWAK calls (

Another frog that one hears calling in the park occasionally is the Green Treefrog (Hyla cinerea), the only treefrog we really see in the park. Despite the name, these bright green frogs are found mainly in reeds, grasses, and other vertical vegetation along the edge of freshwater ponds and marshes. During warm Spring and Summer months the males sing a raucous chorus of nasal KWAK KWAK KWAK calls (

k.

k.

KEK KEK KEK KEK KEK KEK echoing out through the canopy of the trees.

KEK KEK KEK KEK KEK KEK echoing out through the canopy of the trees.