Wildlife Wednesday: Lost Animals of the Coastal Prairie

There was a time, before European settlement of this part of Texas, when the area in and around the nature center would have been tall grass prairie as far as you looked. Most tall trees would have occurred on a few raised areas or along the banks of bayous. Today, 99% of this ecosystem is gone, and along with it, many of the animals that once inhabited this region. Though you may know that large herds of American Bison once roamed this area, and that morning bird song would have been deafeningly loud, you may not know about some of the predators that once prowled the tall grasses of our Coastal Prairies. Today, we’ll have a look at 4 lost species.

While most people think of Ocelots (Leopardus pardalis) as creatures of Central and South American rainforests, these medium sized predators actually inhabit a variety of habitats, including deserts and grasslands, and once roamed our prairies. Today we have an extremely small population of possibly around 50 in the Southern tip of Texas, but they once ranged up the Texas coast all the way to Easternmost Louisiana. These spotted cats were driven to extinction in the state through overhunting and destruction of habitat, but have been reestablished in in the Lower Rio Grande Valley through conservation efforts by landowners, environmental groups, and government agencies, like the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

While most people think of Ocelots (Leopardus pardalis) as creatures of Central and South American rainforests, these medium sized predators actually inhabit a variety of habitats, including deserts and grasslands, and once roamed our prairies. Today we have an extremely small population of possibly around 50 in the Southern tip of Texas, but they once ranged up the Texas coast all the way to Easternmost Louisiana. These spotted cats were driven to extinction in the state through overhunting and destruction of habitat, but have been reestablished in in the Lower Rio Grande Valley through conservation efforts by landowners, environmental groups, and government agencies, like the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

Jaguars (Panthera onca) are another rainforest cat that is actually more variable than many people realize, and may live in a variety of ecosystems, beyond just rainforest. Like ocelots, jaguars once ranged our prairies and bottomland hardwood forests along the gulf coastal part of the state to the Eastern edge of Louisiana. Jaguars were killed off in Texas in the early 1900s, and have not returned to the state since, but they are slowly reestablishing themselves in Southern Arizona. These large powerful predators need a lot of land to roam in, and like ocelots, need to be able to roam back and forth across the border with Mexico, in order to maintain viable hunting grounds and territories.

Louisiana Black Bears (Ursus americanus luteolus) used to range all through East Texas and down the Gulf Coast to Northern Mexico. By the early 1900s, this subspecies of the Black Bear had been made extinct in the state of Texas through overhunting and destruction of habitat. Over the last few decades, conservation and reintroduction efforts in Louisiana have increased the numbers of these endangered bears, and they are slowly reappearing in East Texas forests. We have also recently seen Mexican Black Bears reintroducing themselves into West Texas, in and around the Big Bend area.

Louisiana Black Bears (Ursus americanus luteolus) used to range all through East Texas and down the Gulf Coast to Northern Mexico. By the early 1900s, this subspecies of the Black Bear had been made extinct in the state of Texas through overhunting and destruction of habitat. Over the last few decades, conservation and reintroduction efforts in Louisiana have increased the numbers of these endangered bears, and they are slowly reappearing in East Texas forests. We have also recently seen Mexican Black Bears reintroducing themselves into West Texas, in and around the Big Bend area.

Though we are accustomed to seeing coyotes in this part of Texas, historically, they ranged much further to the West of us, and our native wild dog in this region of Texas was the Red Wolf (Canis rufus). These critically endangered predators were not only hunted to extinction in the state of Texas, but are almost functionally extinct in the wild, only living in parts of the Southeastern U.S. with help from conservation organizations and government agencies. It is not clear that this species will be able to escape total extinction in the wild, as they still face extreme pressure from poaching and habitat degradation in the few areas in which they still occur outside of zoos and assurance colonies.

While its a bit sad to think about, its important to know what we’ve lost, and what we could have again, if we wanted to reestablish our native ecosystems to a more historically natural state. Well, I hope you enjoyed our brief look at a few species we once had roaming the land that the Nature Center now occupies.

Thanks for joining us, and see you soon!

Eric Duran

Staff Naturalist

photographs via: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and Jesse McCarty | Flickr CC

One of the most commonly encountered non-spider arachnids in this part of the state is the Striped Bark Scorpion (Centrutoides vittatus). This is a small scorpion, growing to only about 2.75 inches in total length. They may deliver a painful sting, though the venom is not usually injurious to humans, beyond the obvious pain and discomfort. As with all other scorpions, this species is carnivorous, seizing their prey with front pinching claws, and injecting the prey with venom from the tail stinger. They then spit out digestive juices onto the prey, and suck up the dissolving body of the prey. Maybe a bit gross, but its what they do!

One of the most commonly encountered non-spider arachnids in this part of the state is the Striped Bark Scorpion (Centrutoides vittatus). This is a small scorpion, growing to only about 2.75 inches in total length. They may deliver a painful sting, though the venom is not usually injurious to humans, beyond the obvious pain and discomfort. As with all other scorpions, this species is carnivorous, seizing their prey with front pinching claws, and injecting the prey with venom from the tail stinger. They then spit out digestive juices onto the prey, and suck up the dissolving body of the prey. Maybe a bit gross, but its what they do!

he 3rd animal we’ll look at this week is from a much lesser known group of arachnids called the “whip scorpions”, and here in the U.S. we call them Vinegaroons (

he 3rd animal we’ll look at this week is from a much lesser known group of arachnids called the “whip scorpions”, and here in the U.S. we call them Vinegaroons (

A really awesome spider, found only in the Cypress Pond at the South End of the park, is the Six-spotted Fishing Spider (Dolomedes triton), which is known for running across the surface of the water. These large leggy water walkers prey on a wide variety of aquatic creatures, like: minnows, tadpoles, aquatic insects, and even other spiders!

A really awesome spider, found only in the Cypress Pond at the South End of the park, is the Six-spotted Fishing Spider (Dolomedes triton), which is known for running across the surface of the water. These large leggy water walkers prey on a wide variety of aquatic creatures, like: minnows, tadpoles, aquatic insects, and even other spiders!

one of our most common butterflies in the park. Not actually related to other fritillaries, these butterflies are actually a kind of longwing or Heliconian butterfly. While the adults will feed on nectar from a variety of flower species, the larvae (caterpillars) will only feed on passionvines (Passiflora spp., Left photo). Passionvine leaves are toxic, and in turn the caterpillars are toxic, as are the adults. The bright orange and black coloration acts as a warning. Gulf Fritillaries have a wingspan of about 3.5 inches.

one of our most common butterflies in the park. Not actually related to other fritillaries, these butterflies are actually a kind of longwing or Heliconian butterfly. While the adults will feed on nectar from a variety of flower species, the larvae (caterpillars) will only feed on passionvines (Passiflora spp., Left photo). Passionvine leaves are toxic, and in turn the caterpillars are toxic, as are the adults. The bright orange and black coloration acts as a warning. Gulf Fritillaries have a wingspan of about 3.5 inches.

The Three-toed Box Turtle (Terrapene triunguis) is our most common species of turtle, and is therefore the one you’re most likely to see. As with most box turtle species, they’re terrestrial, and tend to be associated with forested and semi-forested habitats. They are rather omnivorous, feeding on a wide variety of mushrooms, berries, flowers, insects and other small invertebrates. Also like other box turtles, their lower shell (the plastron) is hinged, which allows them to pull inside their shell and then close it up tightly. Three-toed Box Turtles usually have a caramel colored shell, which may have darker markings as well, and the males will will have various colorful markings around the face and legs. Males are larger and have reddish eyes, and the females have yellowish eyes.

The Three-toed Box Turtle (Terrapene triunguis) is our most common species of turtle, and is therefore the one you’re most likely to see. As with most box turtle species, they’re terrestrial, and tend to be associated with forested and semi-forested habitats. They are rather omnivorous, feeding on a wide variety of mushrooms, berries, flowers, insects and other small invertebrates. Also like other box turtles, their lower shell (the plastron) is hinged, which allows them to pull inside their shell and then close it up tightly. Three-toed Box Turtles usually have a caramel colored shell, which may have darker markings as well, and the males will will have various colorful markings around the face and legs. Males are larger and have reddish eyes, and the females have yellowish eyes.

The only species of aquatic turtle that lives in our park is the Red-eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans), which is also one of the most commonly encountered aquatic turtles in the Houston area. This is one of the “basking turtles”, aquatic turtles in the family Emydidae that are often seen basking in the sunshine on pond banks, rocks, and logs. Sliders are ominvorous turtles, but start out their lives as primarily carnivorous, and shift to a more plant based diet as they grow older. Despite the name, the red marks on the sides of their heads do not correspond exactly with the location of the ears. While the shells of the juveniles may be elaborately marked with yellow and green lines, the patterns fade away (eventually to black or dark gray), as they mature. Older individuals may even lose all markings and become totally black (a color condition called “advanced melanism”).

The only species of aquatic turtle that lives in our park is the Red-eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans), which is also one of the most commonly encountered aquatic turtles in the Houston area. This is one of the “basking turtles”, aquatic turtles in the family Emydidae that are often seen basking in the sunshine on pond banks, rocks, and logs. Sliders are ominvorous turtles, but start out their lives as primarily carnivorous, and shift to a more plant based diet as they grow older. Despite the name, the red marks on the sides of their heads do not correspond exactly with the location of the ears. While the shells of the juveniles may be elaborately marked with yellow and green lines, the patterns fade away (eventually to black or dark gray), as they mature. Older individuals may even lose all markings and become totally black (a color condition called “advanced melanism”).

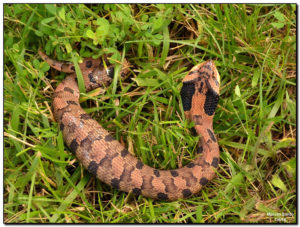

The Eastern Hognose (Heterodon platyrhinos) is one of the few creatures that can eat toads (with their toxic skin). Hognoses are (mildly) rear-fanged venomous, and use those fangs in the rear of their mouths to pop the toads which they eat (toads inflate themselves with air to keep from being swallowed). These snakes are known for spreading their hoods, like a small cobra, and hissing loudly when threatened. If that doesn’t drive away a potential predator, they flip over and play dead (even letting their tongue hang out and emitting a foul death like odor).

The Eastern Hognose (Heterodon platyrhinos) is one of the few creatures that can eat toads (with their toxic skin). Hognoses are (mildly) rear-fanged venomous, and use those fangs in the rear of their mouths to pop the toads which they eat (toads inflate themselves with air to keep from being swallowed). These snakes are known for spreading their hoods, like a small cobra, and hissing loudly when threatened. If that doesn’t drive away a potential predator, they flip over and play dead (even letting their tongue hang out and emitting a foul death like odor).

The Green Anole (Anolis carolinensis) is the most commonly seen native lizard in the park. Also called Carolina Anoles, they are sometimes called “chameleons”, because of their ability to change skin color (various shades of green and brown). However, they are not true chameleons, which are found in Africa, the Middle East, and Southern Europe. Green Anoles are conspicuous lizards and excellent climbers, often sunning, fighting, feeding on insects, courting and mating on the sides of houses, fences, trees, bushes, and yard furniture. The males are easy to identify with their pink dewlaps (throat fans) which they extend when trying to court a female or making territorial displays to other males.

The Green Anole (Anolis carolinensis) is the most commonly seen native lizard in the park. Also called Carolina Anoles, they are sometimes called “chameleons”, because of their ability to change skin color (various shades of green and brown). However, they are not true chameleons, which are found in Africa, the Middle East, and Southern Europe. Green Anoles are conspicuous lizards and excellent climbers, often sunning, fighting, feeding on insects, courting and mating on the sides of houses, fences, trees, bushes, and yard furniture. The males are easy to identify with their pink dewlaps (throat fans) which they extend when trying to court a female or making territorial displays to other males.

Ladybugs are all over the park right now, but we’ve seen mostly Asian Many-spotted Ladybird Beetles in our wildflower gardens and Pocket Prairie. This week, we finally spotted some of our native Convergent Ladybird Beetles (Hippodamia convergens) skulking around various plants, preying on aphids. They are best known for converging in large numbers on logs, rocks, and even the sides of homes in autumn and through the winter.

Ladybugs are all over the park right now, but we’ve seen mostly Asian Many-spotted Ladybird Beetles in our wildflower gardens and Pocket Prairie. This week, we finally spotted some of our native Convergent Ladybird Beetles (Hippodamia convergens) skulking around various plants, preying on aphids. They are best known for converging in large numbers on logs, rocks, and even the sides of homes in autumn and through the winter.

ood Stump Borer (Mallodon dasytomus) grows to about 2 1/2 inches long, and can deliver a painful bite with their large sharp mandibles (though this is not an aggressive species, and only bites when grabbed). They live in and around dead rotten stumps and logs, where they prey on a variety of other insects, especially ants and their larvae. the wood boring larvae (grubs) may take 3-4 years to mature into adults!

ood Stump Borer (Mallodon dasytomus) grows to about 2 1/2 inches long, and can deliver a painful bite with their large sharp mandibles (though this is not an aggressive species, and only bites when grabbed). They live in and around dead rotten stumps and logs, where they prey on a variety of other insects, especially ants and their larvae. the wood boring larvae (grubs) may take 3-4 years to mature into adults!

enal’s Duskywing (Erynnis juvenalis) is one of 2 species of Duskywing (dark colored skippers that keep their wings open and flattened when on a perch), found in our park. The other is the very similar Horace’s Duskywing, though there are many other species of Duskywing across the country. The caterpillars of these skippers feed on oak leaves. They are similar in size to the Checkered skippers, ~3.8 cm wingspan. Duskywings can make themselves rather conspicuous with their darting, climbing, and diving flight patterns, and their habit of sunning out in flat open meadows in plain sight.

enal’s Duskywing (Erynnis juvenalis) is one of 2 species of Duskywing (dark colored skippers that keep their wings open and flattened when on a perch), found in our park. The other is the very similar Horace’s Duskywing, though there are many other species of Duskywing across the country. The caterpillars of these skippers feed on oak leaves. They are similar in size to the Checkered skippers, ~3.8 cm wingspan. Duskywings can make themselves rather conspicuous with their darting, climbing, and diving flight patterns, and their habit of sunning out in flat open meadows in plain sight.